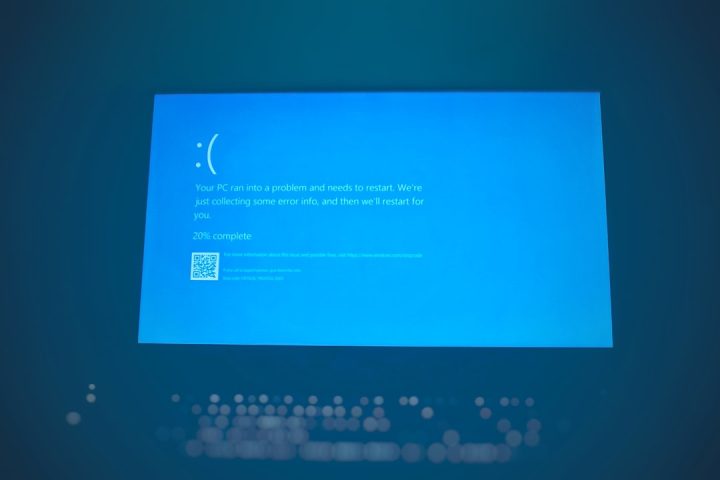

In the world of digital experiences, few messages are more frustrating than the classic: “We have encountered an error—please try again later.” It’s a vague string of words that appears during app usage, form submissions, or content browsing. Unfortunately, while meant to offer reassurance and buy time, such messages often fail users. They are symptomatic of deeper failures in user experience (UX) design—ones that can leave users confused, disoriented, or, worse, gone forever.

This article explores why these types of generic messages are problematic, and provides actionable, trustworthy UX fixes that any product team can implement. Handling errors is not simply about logging bugs or retry logic; it’s about sustaining user trust when things don’t go as planned.

The Problem with Generic Error Messages

Generic error messages serve a functional purpose from a development standpoint. They are catch-all signals for edge cases or service degradation. However, from a UX perspective, they signal failure—not just of the system, but of the experience itself.

- Lack of clarity: The user has no idea what went wrong or how to correct it.

- Loss of trust: Repeated exposure to vague errors can erode confidence in the product.

- Increased support costs: Users may resort to contacting customer support for minor issues.

It’s important to remember that every error message is a bridge between system logic and human experience. When that bridge collapses into a wall of generic text, the connection fails catastrophically.

What Makes a Good Error Message?

Before diving into fixes, it’s important to define what a good error message should do. A trustworthy and user-centered error message will:

- Explain the issue: Clearly state what went wrong, if possible.

- Offer a solution: Give the user clear next steps to resolve the problem.

- Stay friendly and professional: Avoid overly technical jargon or dismissive tone.

- Be visible and non-intrusive: Ensure the error doesn’t block the entire interface unnecessarily.

Think of effective error-handling as customer service through text—an empathetic conversation rather than a dead end.

Common UX Fixes for Error Handling

Below are some of the most impactful strategies for dealing with vague or generic error messages.

1. Use Specific Language

“We have encountered an error” is akin to saying, “Something went wrong—good luck!” If the system knows why a failure occurred, the message should reflect that. Instead of:

“An error occurred. Please try again later.”

Say something like:

“We couldn’t process your payment because the card was declined. Please check your card details or try another payment method.”

Such specificity reduces confusion and helps users take corrective action immediately.

2. Attach a Timestamp or Error Code

For cases where the issue is unexpected or technical, provide an error code or timestamp that users can reference when contacting support. This adds transparency without compromising UX.

Example:

“Unexpected error (Code: X234). Our team has been notified. Please try again in a few minutes.”

3. Provide Retry and Recovery Options

Instead of offering only a vague hope that things will work later, proactively give the user tools to recover. Button options like “Try Again,” “Reload,” or “Go Back” can all increase user confidence that they have control over the situation.

Never underestimate the calming effect of a “Retry” button.

4. Maintain Context and User Input

One of the biggest frustrations users face is having to re-enter lost content after an error. If a form fails on submission, preserve user inputs and highlight only what needs correcting. This signifies respect for the user’s time and intention.

5. Use Visual Cues and Gestures

Color codes (such as red or orange), motion (like shaking a dialog box), or visual icons (like an exclamation point inside a triangle) can help users quickly identify that an error has occurred and guide their attention to where it matters.

Operational Approaches to Improve UX Around Errors

1. Analyze Error Logs with UX in Mind

Error reporting solutions like Sentry or Datadog are not just tools for engineering—they’re valuable for UX teams, too. Analyzing high-frequency user-facing errors can help prioritize which messages need clarity or remediation most urgently.

2. Test Error Scenarios Intentionally

Too often, testing focuses on success states. UX and QA teams should work together to simulate failures like network drops, API latency, expired tokens, or rate limits. Each broken scenario is a chance to improve the user’s experience under stress.

3. Build Error-Ready UI Components

Design systems should include states for errors by default. Components like buttons, modals, cards, or forms must all have fallback scenarios designed. These should integrate error message patterns that align with your brand voice and tone.

The Psychological Impact of Error Feedback

When users encounter errors, especially vague ones, it can cause more than inconvenience—it can generate anxiety, anger, or shame. Humanizing error messages with warmth and empathy doesn’t just build trust; it helps soothe these reactions. For example:

- Instead of “Access denied,” say “It looks like you don’t have permission to view this page. If that seems wrong, please contact your admin.”

- Instead of “Invalid input,” say “Please check your phone number format. We support U.S. and international formats.”

These small differences can have monumental impacts on customer experience.

When is it Okay to Be Generic?

There are rare situations where generic error messages can be justified—for example, in highly sensitive systems (e.g., banking or security) where explaining the cause might reveal exploitable logic. Even then, messages should be paired with contact options or help articles.

In other cases where the true cause is unknown, including a statement that acknowledges the failure and commits to resolution shows responsibility. A message such as:

“Something didn’t work as expected. We’re looking into it. Please try again later or contact support.”

is still more informative and responsible than a lifeless “Error occurred.”

Conclusion

Errors are inevitable, but poor user experiences during those errors are not. Every error message is an opportunity to communicate clarity, restore control, and express empathy. By moving past vague templates like “We have encountered an error—please try again later,” organizations can reduce churn, cut support costs, and—most importantly—build products that users trust, even when plans go awry.

It’s time we stop treating error messages as afterthoughts and begin designing them with the same care as core features. After all, how a product handles its worst moments says more about its quality than how it functions when everything goes right.